Click for 360 tour

In 1789, speaking on behalf of Jewish

emancipation in the French National

Assembly, the Count of Clermont-Tonnerre proclaimed that “Jews should be

denied everything as a nation, but granted

everything as individuals,” adding that

“[t]he existence of a nation within a nation

is unacceptable to our country.”

On the eve of the Revolution some 40,000

Jews lived in France. France kept Jews in

an inferior status, limiting their occupations

and residence and levying special taxes.

In January 1790 the assembly granted

Sephardi Jews full citizenship and in

September 1791 extended citizenship to

Ashkenazi Jews as well. In 1806 Napoleon

challenged Jews to prove that they

deserved the equal status the Revolution

had given them.

Israël-Bernard de Valabrègue

Letter or thoughts of a milord to his correspondent in Paris;

concerning the demand of the Six Corps merchants against

the Jews

London: 1767

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

Born in Avignon, Jewish scholar Valabrègue became an

interpreter at the Royal Library (Bibliothèque du Roi). In this

piece he reacts to the opposition by the Six Corps of Paris,

a powerful trade organization of grocers and furriers, to

admitting Jewish members. Valabrègue argues on this page

that if Jews are allowed to “enjoy all the rights of citizens,

they will suddenly have the soul of a citizen.”

Listen to Sid Lapidus speak about Valabregue, one of the first Jews to hold an official position in France without converting to Christianity.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Abbé Henri Grégoire

Essai sur la régénération physique, morale et politique des Juifs

(An Essay on the Physical, Moral, and Political Regeneration

of the Jews)

Metz: Claude Lamort, 1789

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

A friend of the Jews, Grégoire argued that their

degeneration was not inherent, but rather a result of

their inferior legal status. He believed that Jews could

be regenerated and made citizens.

Proclamation Of The King, On a decree of the national

assembly, concerning the Jews ...

Bordeaux: Michel Racle, bookseller, 1790

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

Read the full text

Read the full text

Letters patent from the king, on a decree of the

National Assembly, concerning the conditions

required to be considered French & admitted to the

exercise of the rights of active citizen

Grenoble: Imprimerie Royale, 1790

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

The 1790 decree issued for the civic emancipation of the Jews concerned

the Sephardi Jews of Bordeaux and Bayonne, not the Ashkenazi Jewish

communities of Alsace and Lorraine. By 1791 Louis (no longer an

absolute, but rather a constitutional monarch) had extended French

citizenship to aliens who had established continuous residence in the

kingdom for five years, provided they owned real estate or married a

Frenchwoman. However, the question of Jews’ citizenship in Alsace and

Lorraine remained “ajourné” (adjourned) or in abeyance.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Jacques Godard

Petition of Jews established in France, addressed to the

National Assembly, 28 January 1790, on the adjournment

of 24 December 1789

Paris: Prault, 1790

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

Christian lawyer Jacques Godard traveled with

Jewish advocate Zalkind Hourwitz between

revolutionary districts, campaigning on behalf of

Jewish emancipation. Godard argues here that

there is nothing in Judaism incompatible with

French citizenship. Godard also states, on this

page, that the Talmud does not encourage Jews to

return to Palestine until the arrival of the Messiah.

Read the full text

Read the full text

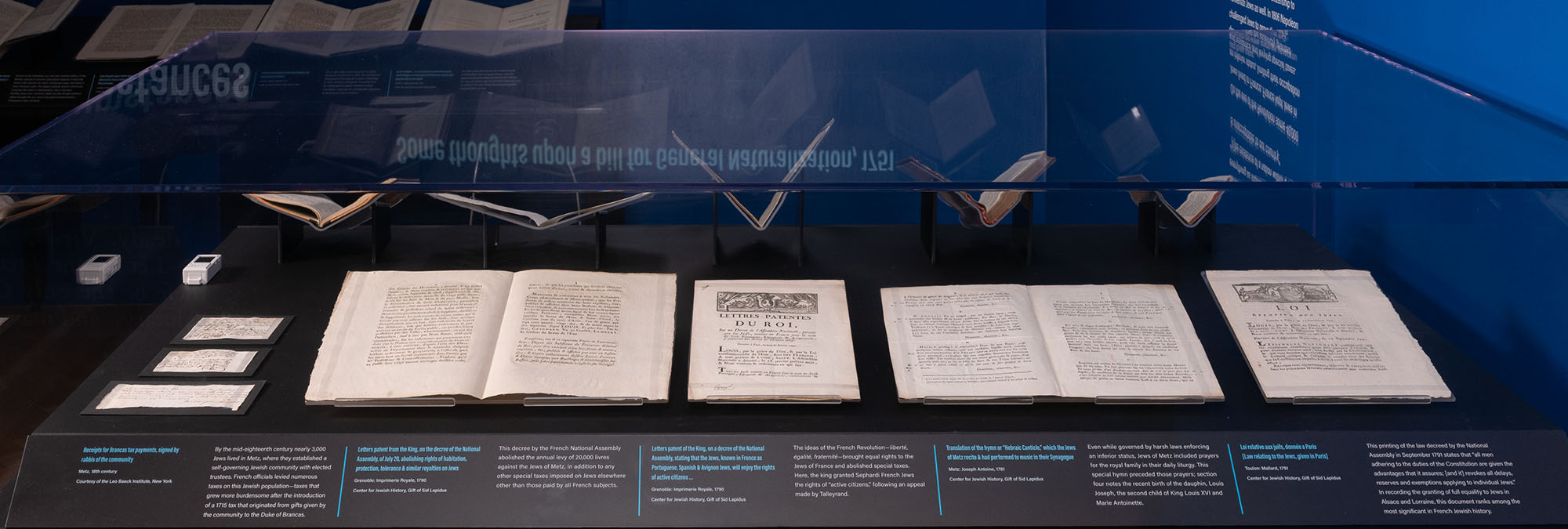

Receipts for Brancas tax payments, signed by

rabbis of the community

Metz, 18th century

Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

By the mid-eighteenth century nearly 3,000

Jews lived in Metz, where they established a

self-governing Jewish community with elected

trustees. French officials levied numerous

taxes on this Jewish population—taxes that

grew more burdensome after the introduction

of a 1715 tax that originated from gifts given by

the community to the Duke of Brancas.

Letters patent from the King, on the decree of the National

Assembly, of July 20, abolishing rights of habitation,

protection, tolerance & similar royalties on Jews

Grenoble: Imprimerie Royale, 1790

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

This decree by the French National Assembly

abolished the annual levy of 20,000 livres

against the Jews of Metz, in addition to any

other special taxes imposed on Jews elsewhere

other than those paid by all French subjects.

Letters patent of the King, on a decree of the National

Assembly, stating that the Jews, known in France as

Portuguese, Spanish & Avignon Jews, will enjoy the rights

of active citizens ...

Grenoble: Imprimerie Royale, 1790

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

The ideas of the French Revolution—liberté,

égalité, fraternité—brought equal rights to the

Jews of France and abolished special taxes.

Here, the king granted Sephardi French Jews

the rights of “active citizens,” following an appeal

made by Talleyrand.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Translation of the hymn or “Hebraic Canticle,” which the Jews

of Metz recite & had performed to music in their Synagogue

Metz: Joseph Antoine, 1781

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

Even while governed by harsh laws enforcing

an inferior status, Jews of Metz included prayers

for the royal family in their daily liturgy. This

special hymn preceded those prayers; section

four notes the recent birth of the dauphin, Louis

Joseph, the second child of King Louis XVI and

Marie Antoinette.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Loi relative aux juifs, donnée a Paris

[Law relating to the Jews, given in Paris]

Toulon: Mallard, 1791

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

This printing of the law decreed by the National

Assembly in September 1791 states that “all men

adhering to the duties of the Constitution are given the

advantages that it assures; [and it] revokes all delays,

reserves and exemptions applying to individual Jews.”

In recording the granting of full equality to Jews in

Alsace and Lorraine, this document ranks among the

most significant in French Jewish history.

Read the full text

Read the full text

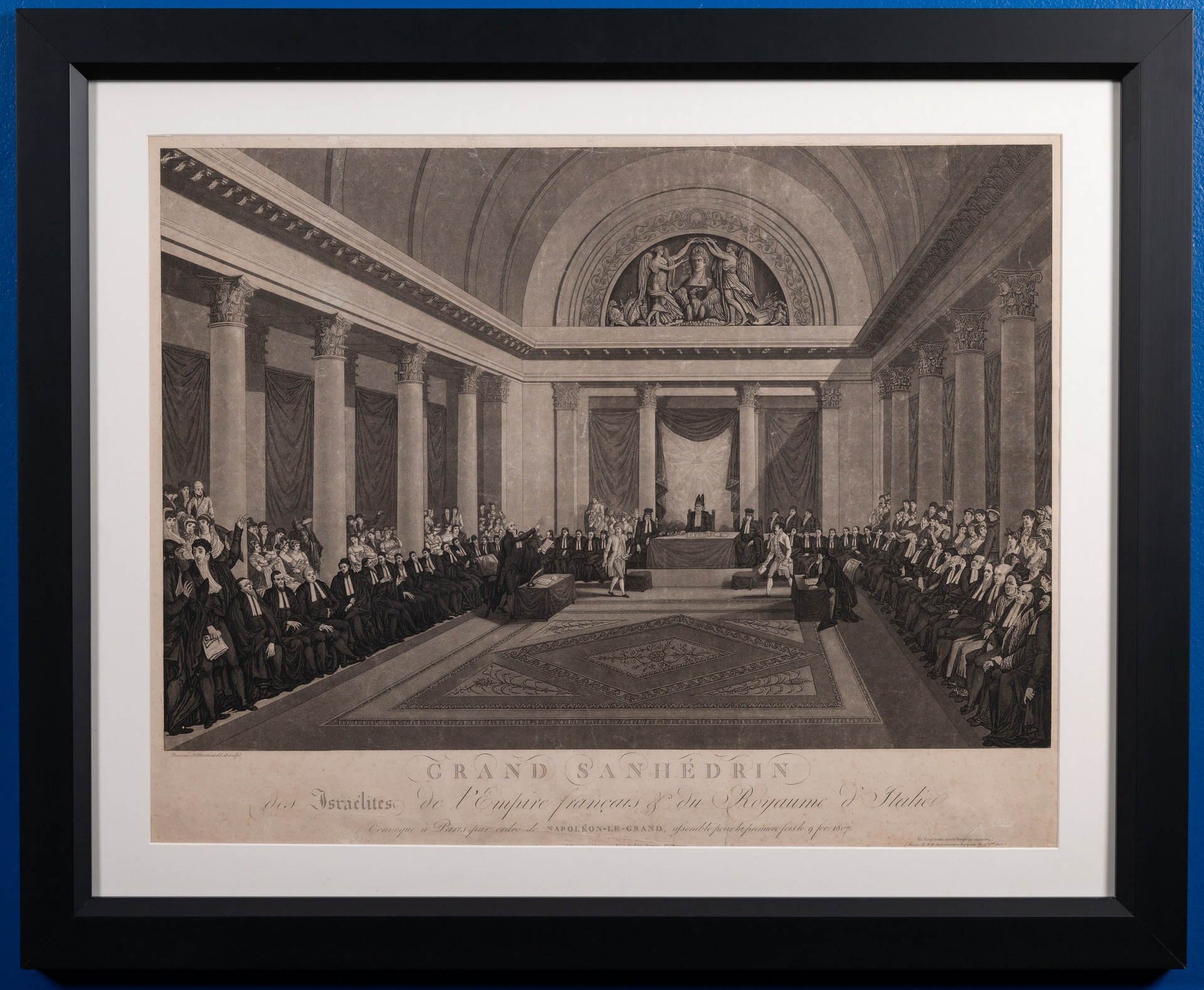

In May 1806 Napoleon Bonaparte convened in Paris the Assembly of Jewish Notables: 111 French, Dutch, and Italian rabbis and Jewish leaders, including Ashkenazim and Sephardim. The emperor posed 12 questions to this assembly, designed to determine whether Judaism was compatible with a postrevolutionary France and the new Code Napoléon. The assembly’s answers expressed the Jews’ willingness to renounce their status as a separate corporation.

Napoleon then convened a “Grand Sanhedrin” in Paris to legalize the assembly’s answers. The Sanhedrin embraced individual rights in place of corporate privileges, claiming that the “political dispositions” of Judaism were “no longer applicable, since Israel no longer forms a nation,” while the “religious dispositions” remained valid and binding.

Decree regarding Jewish usury and the debts of

non-merchant (peasant) farmers in certain regions

of the Empire

Paris: Rondonneau, May 30, 1806

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

With this document Napoleon initiated

the process of establishing the Assembly

of Jewish Notables. This table shows the

distribution of delegates from regions

across France, Italy, and Holland who would

convene in Paris on July 15, 1806.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Proclamation to Jewish communities of

Europe inviting them to send delegates to

the Grand Sanhedrin, 1806

Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish

Theological Seminary

Abraham Furtado

Minutes of the meetings of the Assembly of French

Deputies professing the Jewish religion

Paris: Desenne, 1806

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

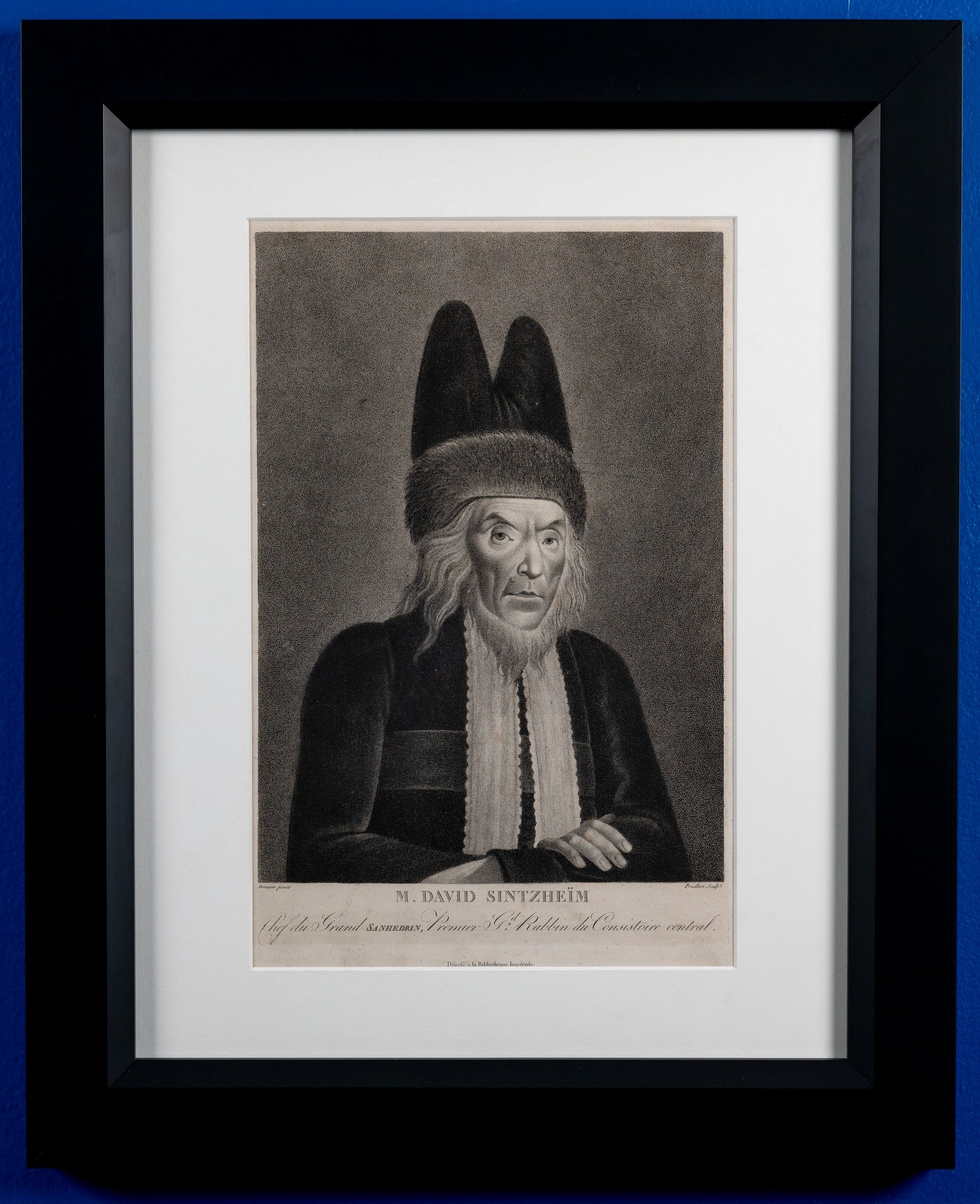

Delegates to the assembly elected as their president Abraham

Furtado, a wealthy Sephardi Jew from Bordeaux. Furtado brought

his political experience and familiarity with Jewish communal

issues to his role. Rabbi David Sintzheim, a notable Talmudist

from Alsace, represented the concerns of Jewish law (halakhah).

Together, Furtado and Sinzheim would lead a committee of 12 to

address Napoleon’s questions and articulate how Jewish law and

Napoleon’s Civil Code were thoroughly compatible.

Listen to Sid Lapidus discuss the timeline for granting citizenship to French Jews.

Read the full text

Read the full text

M. Diogene Tama and F. D. Kirwan (translator)

Transactions of the Parisian Sanhedrin or,

Acts of the assembly of Israelitish deputies

of France and Italy

London: Charles Taylor, 1807

Center for Jewish History, Gift of Sid Lapidus

A rabbi and merchant, Tama was chosen as the

secretary to a delegate of the Assembly of Jewish

Notables. He diligently kept transcripts of the

proceedings and received permission from the French

minister of the interior to publish them. This printed

transcript reflects the tense encounter between

Napoleon and the delegates as they negotiated the

proper behavior for Jews as citizens.

Read the full text

Read the full text

Prayer of the Members of the Sanhedrin, Recited in

Their Assembly Convened in Paris on the First Day of

Adar in the Year 5567

Paris: J. J. Marcel, Imprimerie Impériale, 1807

Yeshiva University Museum, 2008.114

As the members of Napoleon’s Sanhedrin

convened in Paris, they prayed both for the

wisdom to guide them in their task and for

their emperor: “Sustained by your right hand,

Lord, it will be easy for us to realize the purity

of our intentions ... and to bring your holy

laws into harmony with those of the state.”

Medal

In Honor of the Grand Sanhedrin of Napoleon

Denon & Depaulis, Rev:

Dupres; France, 1806

Bronze

The Jewish Museum, New York;

Gift of Samuel Friedenberg Collection, FB 145

Le grand Sanhedrin, 1807

Alfred Aron, engraver and printer

Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological

Seminary

Joseph David ben Isaac Sintzheim,

Chief rabbi of Strasbourg and president

of Napoleon’s Sanhedrin

Prud’hon (engraver); Damane (painter)

Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish

Theological Seminary

As the head of a Strasbourg yeshiva

and a recognized expert in Jewish

law Sintzheim bore the responsibility

for addressing Napoleon’s questions

from the perspective of rabbinic law

(halakhah).